GitHub Apps

GitHub Apps are first-class actors within GitHub. A GitHub App acts on its own behalf, taking actions via the API directly using its own identity, which means you don’t need to maintain a bot or service account as a separate user.

GitHub Apps can be installed directly on organization and user accounts and granted access to specific repositories. They come with built-in webhooks and narrow, specific permissions.

When you set up your GitHub App, you can select the repositories you want it to access. For example, you can set up an app called MyGitHub that writes issues in the octocat repository and only the octocat repository. To install a GitHub App, you must be an organization owner or have admin permissions in a repository.

By default, only organization owners can manage the settings of GitHub Apps in an organization. To allow additional users to manage GitHub Apps in an organization, an owner can grant them GitHub App manager permissions.

GitHub Apps are applications that need to be hosted somewhere. For step-by-step instructions that cover servers and hosting, see “Building Your First GitHub App.”

To improve your workflow, you can create a GitHub App that contains multiple scripts or an entire application, and then connect that app to many other tools. For example, you can connect GitHub Apps to GitHub, Slack, other in-house apps you may have, email programs, or other APIs.

Keep these ideas in mind when creating GitHub Apps:

- A user or organization can own up to 100 GitHub Apps.

- A GitHub App should take actions independent of a user (unless the app is using a user-to-server token).

- To keep user-to-server access tokens more secure, you can use access tokens that will expire after 8 hours, and a refresh token that can be exchanged for a new access token. For more information, see “Refreshing user-to-server access tokens.”

- Make sure the GitHub App integrates with specific repositories.

- The GitHub App should connect to a personal account or an organization.

- Don’t expect the GitHub App to know and do everything a user can.

- Don’t use a GitHub App if you just need a “Login with GitHub” service. But a GitHub App can use a user identification flow to log users in and do other things.

- Don’t build a GitHub App if you only want to act as a GitHub user and do everything that user can do.

- If you are using your app with GitHub Actions and want to modify workflow files, you must authenticate on behalf of the user with an OAuth token that includes the workflow scope. The user must have admin or write permission to the repository that contains the workflow file. For more information, see “Understanding scopes for OAuth apps.”

To begin developing GitHub Apps, start with “Creating a GitHub App.” To learn how to use GitHub App Manifests, which allow people to create preconfigured GitHub Apps, see “Creating GitHub Apps from a manifest.”

OAuth Apps

OAuth2 is a protocol that lets external applications request authorization to private details in a user’s GitHub account without accessing their password. This is preferred over Basic Authentication because tokens can be limited to specific types of data and can be revoked by users at any time.

Warning: Revoking all permissions from an OAuth App deletes any SSH keys the application generated on behalf of the user, including deploy keys.

An OAuth App uses GitHub as an identity provider to authenticate as the user who grants access to the app. This means when a user grants an OAuth App access, they grant permissions to all repositories they have access to in their account, including any organizations they belong to that haven’t blocked third-party access.

Building an OAuth App is a good option if you are creating more complex processes than a simple script can handle. Note that OAuth Apps are applications that need to be hosted somewhere.

Keep these ideas in mind when creating OAuth Apps:

- A user or organization can own up to 100 OAuth apps.

- An OAuth App should always act as the authenticated GitHub user across all of GitHub (for example, when providing user notifications).

- An OAuth App can be used as an identity provider by enabling a “Login with GitHub” for the authenticated user.

- Don’t build an OAuth App if you want your application to act on a single repository. With the repo OAuth scope, OAuth Apps can act on all the authenticated user’s repositories.

- Don’t build an OAuth App to act as an application for your team or company. OAuth Apps authenticate as a single user, so if one person creates an OAuth App for a company to use, and then they leave the company, no one else will have access to it.

- If you are using your OAuth App with GitHub Actions and want to modify workflow files, your OAuth token must have the workflow scope and the user must have owner or write permission to the repository that contains the workflow file. For more information, see “Understanding scopes for OAuth apps.”

For more on OAuth Apps, see “Creating an OAuth App” and “Registering your app.”

Personal Access Tokens

A personal access token is a string of characters that function similarly to an OAuth token where you can specify its scopes.

A personal access token is also similar to a password, but you can have many of them and you can revoke access to each one at any time.

For example, you can enable a personal access token to write to your repositories. To run a cURL command or write a script that creates an issue in your repository, you would pass the personal access token to authenticate. You can store the personal access token as an environment variable to avoid typing it every time you use it.

Keep these ideas in mind when using personal access tokens:

- Remember to use this token to represent yourself only.

- You can perform one-off cURL requests.

- You can run personal scripts.

- Don’t set up a script for your whole team or company to use.

- Don’t set up a shared user account to act as a bot user.

Deploy Keys

You can launch projects from a GitHub repository to your server by using a deploy key, which is an SSH key that grants access to a single repository. GitHub attaches the public part of the key directly to your repository instead of a personal user account, and the private part of the key remains on your server. For more information, see “Delivering deployments.”

Deploy keys with write access can perform the same actions as an organization member with admin access, or a collaborator on a personal repository. For more information, see “Repository permission levels for an organization” and “Permission levels for a user account repository.”

Pros of Deploy Keys

- Anyone with access to the repository and server can deploy the project.

- Users don’t have to change their local SSH settings.

- Deploy keys are read-only by default, but you can give them write access when adding them to a repository.

Cons of Deploy Keys

- Deploy keys only grant access to a single repository. More complex projects may have many repositories to pull to the same server.

- Deploy keys are usually not protected by a passphrase, making the key easily accessible if the server is compromised.

For more information on how to setup and use these, please see our documentation on “Deploy Keys.”

Machine users

If your server needs to access multiple repositories, you can create a new GitHub account and attach an SSH key that will be used exclusively for automation. Since this GitHub account won’t be used by a human, it’s called a machine user.

You can add the machine user as:

- A collaborator on a personal repository (granting read and write access)

- an outside collaborator on an organization repository (granting read, write, or admin access)

- a team with access to the repositories it needs to automate (granting the permissions of the team).

Tip: Our terms of service state:

Accounts registered by “bots” or other automated methods are not permitted.

This means that you cannot automate the creation of accounts. But if you want to create a single machine user for automating tasks such as deploy scripts in your project or organization, that is totally cool.

Pros of a Machine User

- Anyone with access to the repository and server can deploy the project.

- No (human) users need to change their local SSH settings.

- Multiple keys are not needed; one per server is adequate.

Cons of a Machine User

- Only organizations can restrict machine users to read-only access. Personal repositories always grant collaborators read/write access.

- Machine user keys, like deploy keys, are usually not protected by a passphrase.

For more information on how to setup and use these, please see our documentation on “Machine users.”

Which should you use?

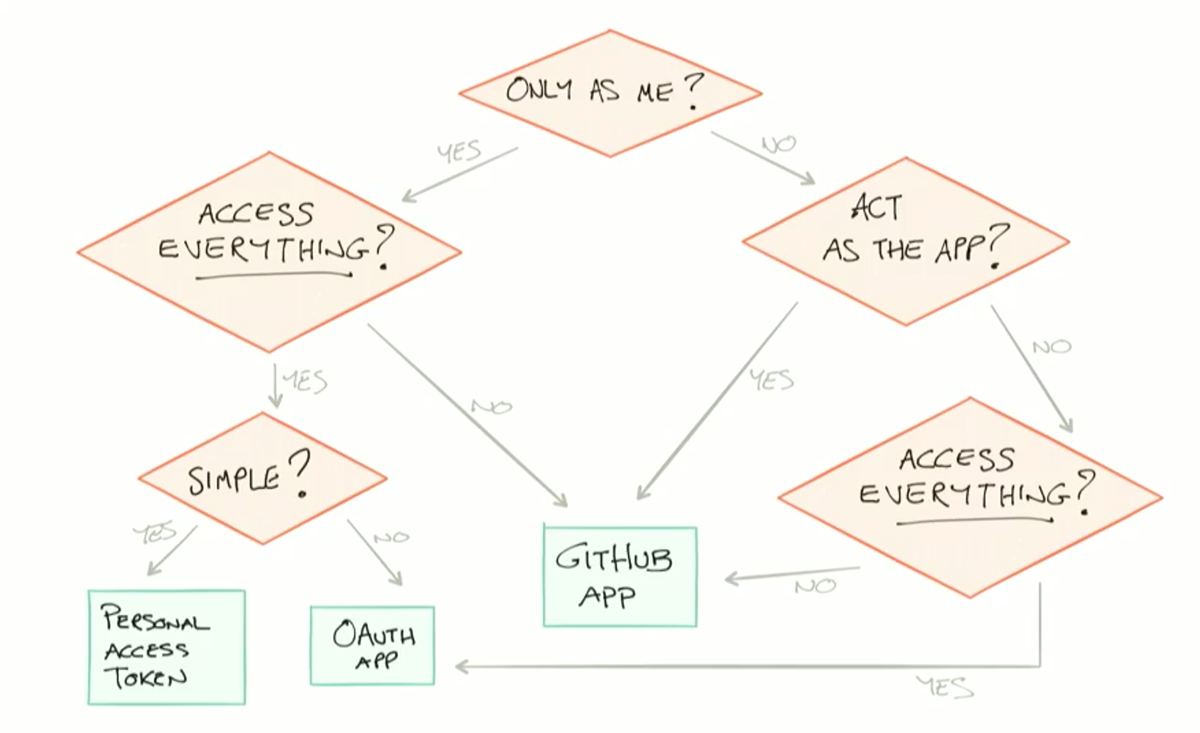

Before you get started creating integrations, you need to determine the best way to access, authenticate, and interact with the GitHub APIs. The following image offers some questions to ask yourself when deciding whether to use personal access tokens, GitHub Apps, or OAuth Apps for your integration.

Consider these questions about how your integration needs to behave and what it needs to access:

- Will my integration act only as me, or will it act more like an application?

- Do I want it to act independently of me as its own entity?

- Will it access everything that I can access, or do I want to limit its access?

- Is it simple or complex? For example, personal access tokens are good for simple scripts and cURLs, whereas an OAuth App can handle more complex scripting.

NIH GitHub Resource Center

NIH GitHub Resource Center